The announcement of Phillip Glass as the 11th recipient the Glenn Gould Prize this past April 14 gives us an opportunity to remember that Glenn Gould was himself an artist who walked amongst us. Although he was someone who changed the world of music in a number of significant ways, the fact remains that he was a person who lived in Toronto, who had friends and colleagues here, myself included, and who was always just a phone call away. He was an indisputably extraordinary individual, but to those of us who were close to him he was just “Glenn.”

The circumstances of our first meeting are typically Gouldian. There was no introduction, no “Hello, I’m David” or corresponding, “Hello, I’m Glenn.” Rather, it came through one of Glenn’s patented devices for getting to know and sizing up another person, namely The Guessing Game.

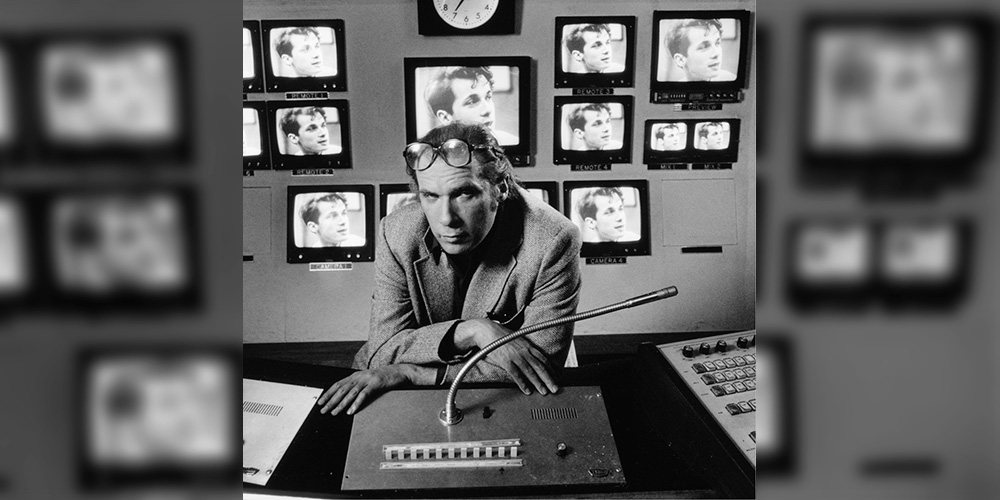

I was the junior producer of the CBC Radio Music Department, having joined the team in January of 1973. It was now early 1974, and although Glenn was never seen in the office during the working day, there were hearsay reports of his nocturnal visits via conversations with veterans of the department. Naturally, as the low man of the Radio Music team, I was keeping late hours, learning the job and just getting work finished.

On that particular February evening, a man suddenly appeared at the entrance to the cubical where I worked. He resembled Glenn Gould, but scruffy — not the shined-up PR photo version I might have expected. His first words were, pretty much exactly, “Excuse me, but if I were to ask you about a certain work, a concerto choréographique for piano with an ensemble consisting of a woodwind octet, brass trio, tympani, string sextet but without any violins, and which was composed for a private occasion in a stately home in 1929, what work would you guess that it was?” Given that I had only recently programmed a recording of the Francis Poulenc Aubade in one of the daily shows I produced, (Sounds Classical with host de B. Holly), I immediately answered that it sounded like that was precisely the work in question. Having passed the test, I was accepted into the fraternity. Our friendship, too, was kindled in that moment.

The conversation went on, and covered such topics as his views on French piano music and why he tended to avoid it. He explained that the Poulenc work in question was chiefly driven by melody and rhythm, which he liked, and unlike the Impressionists whose music he felt was narcissistic in its obsession with sonority. He explained why he had recently recorded two works by Bizet, calling him “The most Wagnerian of the French Romantics.” He preferred music that embraced counterpoint, pointing out that, as long as the voices and rhythms were clear, the message of the music was not beholden to the sonic circumstances through which it would be played, recorded and heard. In a following conversation soon after he revealed that his compositional avatars (his word) were J.S. Bach, Richard Strauss and Arnold Schoenberg. It was their respective achievements in the art of counterpoint that had earned them this ultimate standing in the pantheon of Glenn’s heroes.

Not long after that initial conversation I received further confirmation that I had passed the test embedded in Glenn’s guessing game. He asked me if I would be willing to work with him as his producer for a series of 10 radio programs in honour of the approaching centennial of the birth of Arnold Schoenberg. No sooner had I agreed, it was revealed that the series had already been granted the stamp of approval from Radio Music’s senior management. This was to be a series of weekly one-hour radio programs in which Glenn would survey the music of Schoenberg in “conversation” with Kenneth Haslam, a CBC Radio staff announcer. The quotation marks are there because this would be an entirely scripted conversation, written by Glenn, even the alleged opinions and interjections of Mr. Haslam. And most of Glenn’s recordings of Schoenberg’s piano music would be included, such as the Suite, Op.25; the Piano Concerto; the Phantasy for Violin with Piano Accompaniment, Op.47; the Ode to Napoleon, Op.41 as well as the major orchestral, chamber and choral works. It was a fascinating and engaging production, laden with tightly packed information about Schoenberg’s music and insights into Glenn’s understanding of it. And there were interviews with exceptional individuals whom Glenn persuaded to share their knowledge of Schoenberg, including conductor Erich Leinsdorf, choral scholar Dr. Denis Stevens, biographer and musicologist, Henry-Louis de La Grange (the founder of the Bibliothèque Gustav Mahler) and composer John Cage who was once Schoenberg’s pupil.

These interviews were fascinating not only because of their erudite participants, but also because they were not staged in the least. Glenn’s interview with John Cage, for example, included some of the well-known stories of Cage’s own relationship with Schoenberg, such as his admission that he had “…no feeling for harmony,” to which Schoenberg responded that without a feeling for harmony Cage would come to a wall and not be able to get through it. Cage responded:

“…well I’ll simply bang my head against that wall.” The interview also contained references to several composers other than Schoenberg. Cage mentions Anton Webern, Henry Cowell, Morton Feldman and even Erik Satie in ways that relate to Schoenberg and his approach to composition. At the end of the Cage interview, Glenn resorts to another of his trademark devices, which he called, “One of those really dumb, hopelessly hypothetical questions to which there is no answer, namely, what would Schoenberg’s reaction be if he could come back and survey the musical scene of 1974.” Following peals of uncontrollable laughter, Cage responded, “I’m afraid he’s stayed away too long to come back now. I think he would be absolutely shocked. Had he come back a little sooner he might have corrected our evil ways.” The other interviews were equally candid and revealed their subjects’ common willingness to open up and share their thoughts with Glenn, an artist they respected, trusted and admired.

Glenn was a person who was equally at ease with all of his various means of communicating, from guessing games, to really dumb, hopelessly hypothetical questions, to broadcasting, documentary making and to performance and recording.

To expand on just how this experience of working with Glenn at the beginning of my 40-year CBC Radio career affected the experiences and productions that came after, well, that’s, as they say, another story.