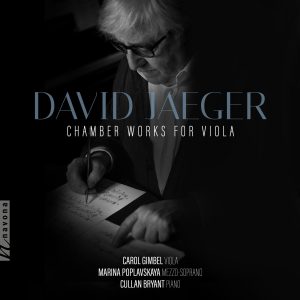

CHAMBER WORKS FOR VIOLA from composer David Jaeger gathers together some of Jaeger’s most defiantly creative compositions and demonstrates the vast possibilities of the viola and the chamber music genre as a whole. Jaeger’s music will surely remind listeners — and perhaps even some other composers — of the rich tonal palate the viola offers.

Today, David is our featured artist in “The Inside Story,” a blog series exploring the inner workings and personalities of our composers and performers. Read on to learn about his natural abilities in both science and music, how they serve each other, and how they led to a fruitful career in broadcasting…

If you weren’t a musician, what would you be doing?

My two constant preoccupations have been music and science. I think the element of my being that links the two is that of curiosity. I have always been curious about how things work, whether it be the fine, innermost workings within the structure of a musical composition, or an understanding of how electrical forces work in a semiconductor. I have always loved exploring and solving technical issues, both artistic and scientific.

At about the same young age as I began to study keyboard performance, I was already reading about chemistry and physics. In Junior High School, I joined the band, and I had my first peek inside a chemistry lab. I learned to play the trumpet, soon achieving the first chair in the band. And on weekends, I would participate in science fairs, occasionally winning first prize for my projects. The trend continued through high school, and I began to compose.

When it was time to apply for university, I took the S.A.T exams, like everyone else. I scored 800 in both physics and chemistry. And so I developed an interest in electronic music, which was probably the most logical way to combine my interests.

If you could collaborate with anyone, who would it be?

My artistic and professional lives have, in fact, been highly collaborative. When I was in graduate school at the University of Toronto, I joined forces with three other composers who, like me, were studying electronic music in what was, at the time, one of the most important electronic music studios in North America. We created the Canadian Electronic Ensemble, with the purpose of bringing the electronic music medium — at the time a largely studio-bound art form, into the performance arena. The CEE is still active today, and has created a great legacy over more than 50 years.

My training in electronic music led me to a career in broadcasting with CBC Radio. It was through my radio work that I learned the true essence of collaboration, as everything we did to make our broadcasts involved working with teams of talented composers, performers, writers, and technicians. I was able to collaborate with people like Glenn Gould, Thomas Ades, Gavin Bryars, Morton Subotnick, Toru Takemitsu, Judith Weir, and many other great musical minds.

In my composing life, I have found great inspiration from my collaborations with poets, and my most recent works owe a great debt to poets such as David Cameron, Bruce Whiteman, and Seán Haldane.

What advice would you give to your younger self if given the chance?

I would simply say: Stay your course — it’s all going to work out!

I have always followed my instincts, both artistically as well as professionally. I feel that being true to yourself is the only way forward. Decisions in life and in one’s work are rarely easy, and of course, I experienced times when the path ahead was not so clear. But I always felt there was no real option other than to listen to the voice inside, and to work as hard as possible to follow it.

As an emerging composer, I felt I needed to give myself permission to try things that were not conventional. This is how I developed my voice. Of course, starting out, we tend to model ourselves on what we see in existing work that we admire. But to communicate your own point of view through your creative voice, it’s clear you need to believe in your own message. And whenever your works are shared with an audience, there’s an opportunity to validate the truth in what you have to say.

Now that I have a substantial canon of my own creations, I can confide with my younger self, and say, listening to yourself was the right thing to do.

What emotions do you hope listeners will experience after hearing your work?

In general, I always hope that listeners will become aware of the things my music reveals that are fresh and new. I think it’s fair to say that the emotional responses to my work are not merely the reactions that the compositions themselves evoke, but also a result of the interpretations by the performer(s). I always strive to make it clear to my performers that I allow them great interpretive freedom with my scores. I would rather hear the response of a performing artist who “believes” in what they’re playing, than a routinely correct following of the notes. It is, after all, these living performers who breathe life into those dots on the page. And they do so magnificently!

The works on this album tend towards the darker side of the emotional scale, though not exclusively so. There are some lighter moments, which hopefully do help to create a balance in the range of moods throughout the listening experience. Certainly those movements that derive directly from poetry are more of a reflection of the personalities of the poets I’ve collaborated with: the extraordinary expressions by the Scottish poet, David Cameron, and the words of the polymath viola soloist, Carol Gimbel.

Where and when are you at your most creative?

My composing studio is any and everywhere I find myself when the act of creating music is ripe for completion. And it can and does happen at unexpected times and places, even on airplanes during intercontinental flights. But the most usual place I compose is at home, in my kitchen, and one end of the table where my laptop and my playback equipment sits, ready to respond to what I need it to do.

But in general, I think it’s safe to say I am a nocturnal being, creatively speaking. Most of my music has been composed as the day comes to a close. I like to settle into a creative project late at night, when the house falls silent, as well as the city around it. The quiet represents something waiting to be filled, and the churning in the creative cauldron inside me is constantly in a state of wanting to empty itself, to get the thoughts out of my mind and onto the page. It’s generally between the hours of 10:00 pm and 2:00 am that this process is fulfilled.

This is not to say that I have nothing to say, creatively, during other times – it does happen!

What’s the greatest performance you’ve ever seen, and what made it special?

I was involved in the CBC Radio Network broadcasts of the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra’s New Music Festival from 1991 to 2007. It’s a remarkable festival that continues to the present day. In 2004 we had the thrilling experience of broadcasting a performance of Styx by Giya Kancheli (1935 to 2019), a composer from the Republic of Georgia. Styx is a concerto for solo viola, choir and orchestra. On this occasion the brilliant Australian violist and composer, Brett Dean played the solo viola part, and Andrey Boreyko conducted.

Kancheli’s music is constructed on an expansive sonic palate, and this particular work possesses perhaps the largest dynamic range I have ever experienced, from pppp to ffff. The orchestration is vivid — it is a work filled with deeply passionate emotions, ranging from the most tender to the most violent and tragic expressions possible, I feel, from a human soul.

Dean, Boreyko, the orchestra, and choir delivered a performance on this occasion that exceeds any other recorded performance of the work I have yet to hear, even though there are several recordings available. I will never forget it!